Singapore is a small country surrounded by oceans, but it has a huge appetite. One of the things that we love best about Singapore is its hawker food culture.

Hawker food plays a much greater role than just filling our bellies—it is a legacy that unites all Singaporeans. Hawker culture has come a long way from its humble beginnings in the 1800s, and the modern incarnation of hawker food continues to evolve alongside Singapore’s ever-changing landscape. It’s not just about food or the flavour—hawker food culture goes beyond that. It’s about people—the people who create it and the people who enjoy it.

The history of hawker food culture in Singapore is deeply intertwined with the country’s history. Let’s take a closer look at this beautiful saga.

The History of Hawker Food Culture in Singapore

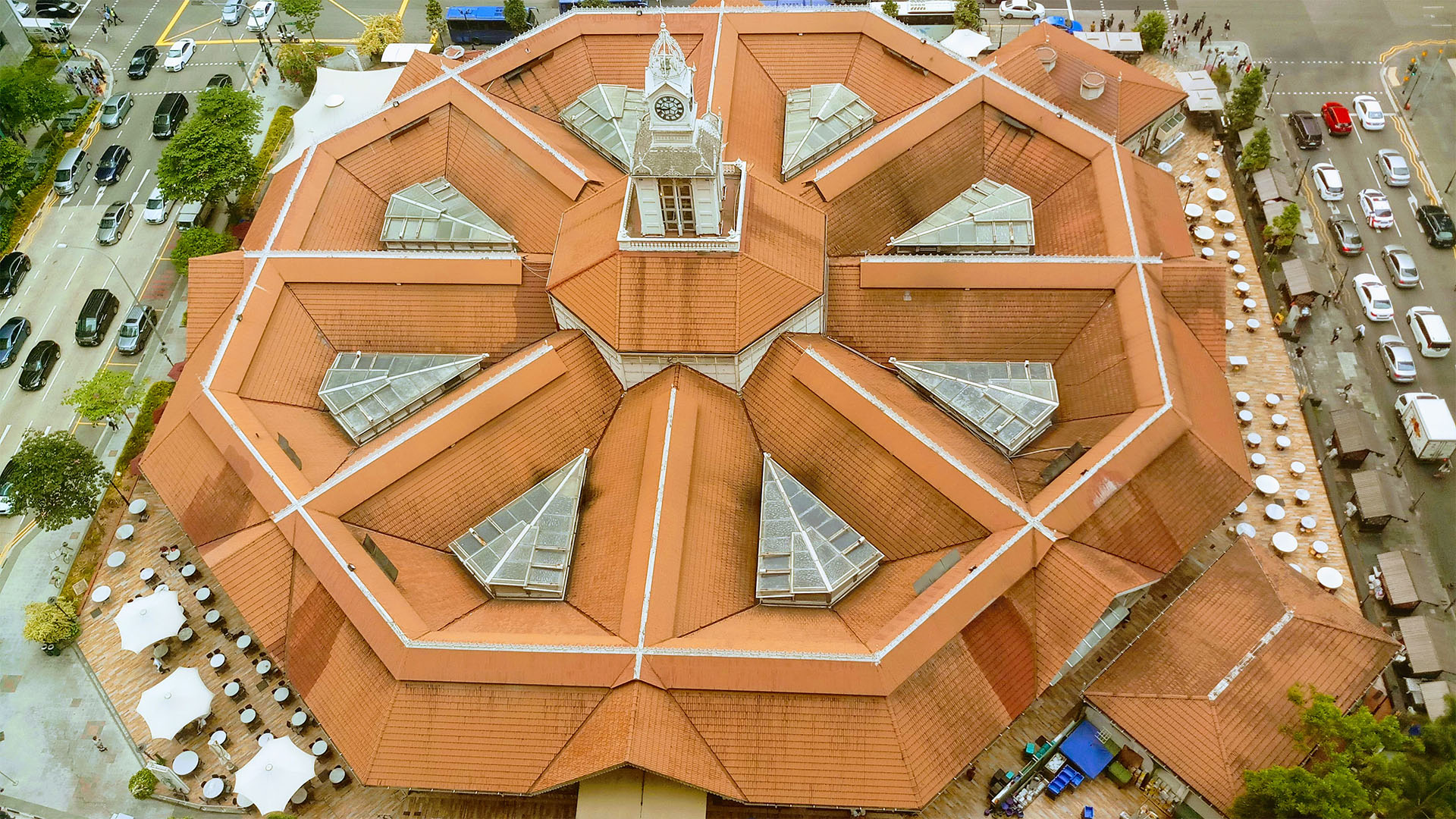

It all started back in the mid-1800s when quick and affordable meals on street sidewalks were in big demand and the early migrant population provided exactly what the masses needed. Considering makeshift stalls were built anywhere there were people, from town squares to parks, you can just imagine how aromatic the air around these places was.

A hundred or so years later, from 1968 to 1986, the government brought these individual stalls under one big roof—the birth of the hawker centres we have today. The dining experience has improved drastically, we now have chairs and tables in one big vibrant communal space and we’re out of the indifferent bustling crowds. What’s more, we now have such huge options of food to eat! These individual menus have come together to build one centre of such diverse menus on the planet. Anywhere you look, there’s food and people everywhere. It’s more than your typical food court, it’s a gathering of a nation.

Today, more than 110 hawker centres have been built in Singapore and there seems to be no decline in the demand for these community dining rooms as more centres are expected to be developed in the next few years.

Hawker Centres’ Most Famous Food Options

When we say hawker centres offer possibly one of the biggest menus on earth, we mean it. From Chinese to Indonesian, Malaysian to Indian, these menus have food that is backed by a long history of their own.

Take the Kaya Toast, for example.

Kaya toast is a delicacy made up of toast slices slathered with kaya (coconut jam) and topped with butter or margarine. It’s usually served with coffee and soft-boiled eggs. The dish is typically served during breakfast in Singapore. It is extensively accessible in food chains such as Ya Kun Kaya Toast, Killiney Kopitiam, and Breadtalk’s Toast Box, and it became integrated into Kopitiam (coffee shop) culture, and it is also deeply embedded in the history of hawker centers due to its popularity.

The kaya toast dish is thought to have been invented by Hainanese immigrants who adapted what they had previously cooked while serving on British ships stationed at harbours during the Straits Settlements period. They were integrated into kopitiams that were opened in the 19th century by Chinese cooks to serve the demanding need of the European working population.

Today, hawker centre stalls like the Ah Seng (Hai Nam) Coffee at Amoy Street Food Centre, a hawker centre located at 7 Maxwell Road Singapore, still offer kaya toast.

Another food offering in hawker centres that are loved by Singaporeans is the Char kway teow—a stir-fried Chinese-inspired rice noodle dish from Maritime Southeast Asia. The noodles are fried in garlic, sweet soya sauce and lard, with ingredients such as egg, Chinese waxed sausage, fishcake, beansprouts and cockles.

Despite its Hokkien name, this stir-fried noodle dish is thought to have originated in Chaozhou in China’s Guangdong region and is connected with the Teochew community. Char kway teow began as a straightforward dish of rice noodles fried in fat and dark soy sauce for the common man. The original flat noodle dish had rice vermicelli, which was eventually replaced by yellow wheat noodles.

Other famous dishes are Fishball Kway Teow Mee, Fried Oyster Omelette, Briyani and Fried Kway Teow.

Consider the variety of hot beverage options: tea and coffee come in an incredible number of variations. Bid farewell to two sugars and milk. And good morning to rich condensed milk with masala spices and ginger, steeped before being poured over shaved ice or ‘pulled’ from a great height. Seniors congregate each morning to peruse their papers while sipping from saucers, an old and creative way to cool down their steaming beverage. Young or old, hawker centres have clearly affected the nation’s everyday routine. Hawker culture is a beautiful and intricate fabric of interwoven individual histories, brought together by people for the people.

Preserving and Sustaining Hawker Culture in Singapore

Hawker culture as we see it today is in its vibrant glory thanks to the collective efforts of many—the hawkers, the community and the government. Together, these people and their love for the “foodie” culture have boosted the culture to the limelight of Singapore living. And with UNESCO‘s decision back in the year 2020 to classify the country’s hawker culture as an intangible cultural heritage of humanity, the hawker culture has made its way to the international scene.

But what does it take to preserve such rich culture that is obviously not immune to the societal impacts occurrences such as the COVID-19 pandemic bring?

The recent years saw the world collectively halting to a pause, affecting millions of business owners across the globe including the hawker businesses of Singapore. With most people choosing to order in instead of going out and frequenting dine-in stores due to the threats of the pandemic, hawker businesses were drastically affected. The rise of online food delivery apps like foodpanda, GrabFood, Oddle and Deliveroo also contributed to the decline in walk-in customers as the food delivery technology encourages people to order their meals from popular restaurant chains and establishments available.

While it is possible for hawker stores to go onboard with these delivery apps, knowing most hawker stores are owned, managed and ran by the older generations, it is really difficult to have them acquainted with such technology.

So what is being done to preserve the hawker culture and provide inclusivity in this digital age?

Well, the National Heritage Board might just have the answer. The NHB has collaborated with government organizations, hawkers’ associations, and food experts to document Singapore’s hawker centres and food, as well as supporting a number of ground-up initiatives.

For example, in 2017, the National Heritage Board and National Environment Agency performed research on 12 hawker centres, examining their history and architecture as well as their social value in relation to their surrounding communities. To tell the history of these hawker centres, storyboards have been installed. It is important that the community understands the roots of this rich culture which then will encourage them to value it, sustaining it for more years to come.

The government of Singapore is hands-on in its efforts. In fact, in mid-2020, it launched initiatives like the Hawkers Go Digital scheme to help hawkers cope with the pandemic. The project facilitates the education of hawker business owners in terms of establishing their online brand as well as adopting the online delivery platforms for their businesses. This initiative also involves the adoption of a unified e-payment solution called SGQR.

Private companies like Grab also have contributions of their own—implementing programs like the Hawker Centre 2.0 which aimed to effectively assist hawker businesses in going digital by reducing their commission rate.

More and more projects are starting to manifest in Singapore in its efforts to safeguard and preserve hawker culture. There are programs that seek to educate hawker businesses in developing a sustainable commercial model and even programs that provide incentives to old and new hawkers.

Initiatives like this are helpful in providing some well-needed relief to the hawkers during such trying times. Which brings us to another question, what can individuals such as yourself do to aid in the preservation of hawker culture?

Effective preservation efforts must be ground-up and you as an individual can help. After all, the hawker culture will not be where it is if not for the patrons. Remember, it is a collective effort. Singaporeans as a society must cherish the hawker culture that we have. It must begin with our children, who must be encouraged to consume hawker food and to be proud of our local cuisine. Governmental incentives can only go far. It is the continuous public support for hawker food that will encourage younger hawker generations to go into the business since it is sustainable.

Indeed, it takes the entirety of Singapore to preserve the hawker culture. And with the recent UNESCO recognition, we hope it inspires us to make our own efforts and also promotes Singapore’s tourism internationally.

The story of Singapore’s food culture is as scattered and diverse as the products traded within our borders. It’s a historic tale and a saga that yields insights into our country’s past, its people’s history, and their interactions with their changing environment.